Background:

The number of people who have irritable bowel diseases (IBDs) and the number of obese people has been increasing since the 1940s (Jin, J. et al, 2021). It has been reported that the number of people diagnosed with IBDs has consistently increased at a varied rate of 1.2% to 23.3% per year from the 1930s until 2010 (Molodecky, N. A. et al. 2012). There are many factors that could lead to this increase in IBDs and obesity diagnoses, alterations to diet, changes to culture, and a further understanding of IBDs and obesity. Irritable Bowel Diseases (IBDs) are incurable and can involve the inflammation of any part of the digestive tract (Halfvarson, J. et al. 2017). Examples are Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative Colitis (UC) (UCLA Health). Crohn’s disease involves inflammation in the digestive tract and ulcerative colitis involves inflammation in the rectum and colon (UCLA Health). Obesity can also alter levels of inflammation, and in past studies, obesity and the level of helpful versus unhelpful gut microbes have been found to match in a predictable way (Jin, J. et al, 2021. Franzosa, E.A. et al. 2019).

The paper, “Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease” by Eric A. Franzosa et al. (2019) helped form the premise for the further research done in this follow up study. In their paper Eric A. Franzosa et al. (2019), established an association between microbiota diversity and IBDs, where microbiota diversity refers to the proportion of bacteria in a given area broken up into different taxonomic groups. However, despite the established link between the microbiome and IBDs in adults, the lack of data on teens with IBDs leaves an ambiguity in our understanding of the gut microbiome and its impact on IBDs.

Central Question:

This study attempts to find an association between gut microbiome in teens and inflammation caused by IBDs and obesity.

Evidence:

In “Adolescent gut microbiome imbalance and its association with immune response in inflammatory bowel diseases and obesity” written by Minjae Joo and Seungyoon Nam and published in 2024 , data was analyzed from 202 people based on four personal gut characteristics: healthy, obesity, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. The datasets analyzed in this study was a re-analysis of existing data openly available in the Sequence Read Archive, a database full of microbe and host information. Using the given number of estimated bacteria and their taxonomic family, a significant difference was found in microbiota diversity between ulcerative colitis (UC) and obese (Ob) samples, crohn’s disease (CD) and Ob samples, and Ob and healthy control (HC) samples.

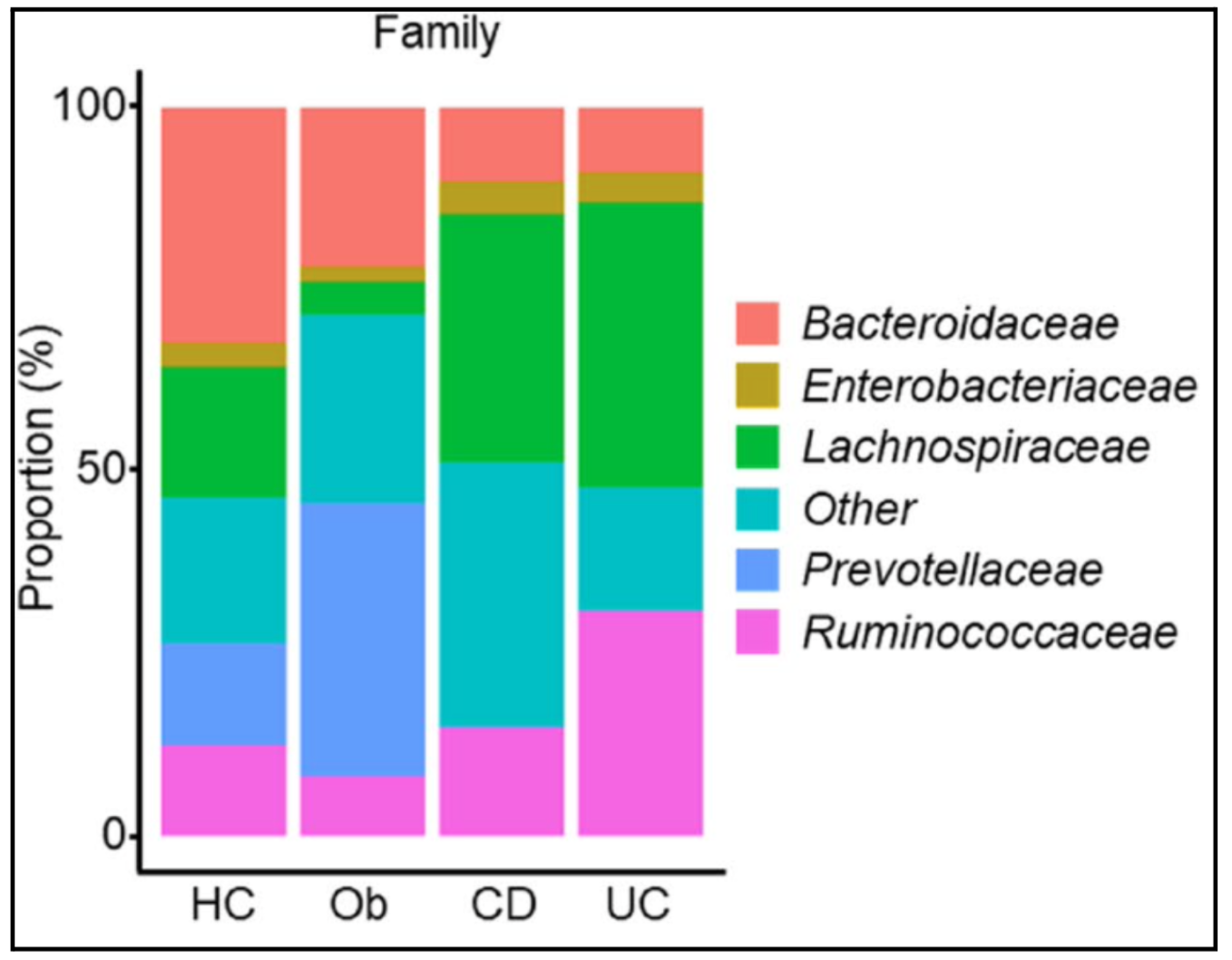

Taxa levels classify living things from broad to specific: domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. Each step narrows the similarities between organisms, with species being the most specific. In figure 1, family level taxa are visualized and the differences in microbiota diversity can be seen. The bottom axis is the different study groups and the side axis is the proportion of the estimated gut microbiome made up by each family of bacteria. From the figure, the difference in bacteria family proportions in the obese sample is visible from the healthy control, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis.

Observed in figure 1, the Ob group had a higher level of Prevotellaceae and lower level of Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae compared to healthy teens; it has a larger light blue bar compared to HC and a small pink and green bar. The IBD group had higher levels of Lachnospiraceae and lower levels of Bacteroidaceae and Prevotellaceae compared to healthy adolescents; CD and UC had a larger green bar than Ob and HC and a smaller light blue and salmon colored bar. Specifically, the UC group had higher levels of Ruminococcaceae compared to the other groups; it has a larger pink bar than any other group.

These are observable changes in microbiota diversity at the family level. At face value these changes don’t indicate positive or negative change in health, figure 1 just creates a visual representation of the diversity found in the data. Thus, supporting the authors claim that teens with IBDs and obesity have an association with gut microbiota changes.

Areas of Future Research:

An area of further research would be to perform fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) from healthy teens to teens suffering from IBDs or obesity. There is an imbalance in gut microbes in people suffering from autoimmune disorders and obesity, it might be beneficial for their gut microbiome to perform FMT as it could improve the imbalance found in the gut microbiota causing a potential reduction in symptoms associated with IBDs and obesity (Xiang, W. et al, 2023).

Another area for further study is finding the connection between the microbiome diversity in teens with IBDs and adults with IBDs. From this study, the taxa of bacteria found in teens with IBDs does not overlap with the taxa of bacteria most abundant in adults with IBDs (Schirmer, M. 2019). In the paper, they discuss how hormonal changes influence the gut microbiome, possibly impacting the bacterial abundance, but I would like to see further research into the microbiota transition over time and maybe a stronger link between puberty hormones and gut microbiomes of IBD affected patients.

Further Reading:

“Your Gut Microbiome: The Most Important Organ You’ve Never Heard Of” is a Ted Talk where Dr Erika Ebbel Angle discusses the importance of the gut microbiome. She stresses the importance of the gut microbiome and its associated positive effects as well as the general outline of how to maintain a healthy gut microbiome. For further understanding of the link between the gut microbiome, obesity, and the immune system, consider watching the youtube video “Linking the Gut Microbiome, Obesity, and the Immune System” which is a paper review video that details some specifics on how microbe variation can impact physical health.

In references, there are two papers, “Distinctive Gut Microbiota in Patients with Overweight and Obesity with Dyslipidemia and its Responses to Long-term Orlistat and Ezetimibe Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Open-label Trial” and “The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity” that are both reference articles for the paper being discussed (Jin, J. et al., Wu, H. J. et al.). They go more in depth on the link between obesity and autoimmune disorders with the gut microbiome of adults. It can be helpful for further understanding of the discussed paper as they add a different perspective and different details regarding study design and variables taken into account.

References:

American Society for Microbiology: (2019, July 31). Linking the Gut Microbiome, Obesity, and the Immune System [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4kYhRPbiOyg

Franzosa, E.A., Sirota-Madi, A., Avila-Pacheco, J. et al. Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol 4, 293–305 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0306-4

Halfvarson, J., Brislawn, C., Lamendella, R. et al. Dynamics of the human gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol 2, 17004 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.4

Jin, J., Cheng, R., Ren, Y., Shen, X., Wang, J., Xue, Y., Zhang, H., Jia, X., Li, T., He, F., & Tian, H. (2021). Distinctive Gut Microbiota in Patients with Overweight and Obesity with Dyslipidemia and its Responses to Long-term Orlistat and Ezetimibe Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Open-label Trial. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2021.732541

Minjae Joo, & Seungyoon Nam. (2024). Adolescent gut microbiome imbalance and its association with immune response in inflammatory bowel diseases and obesity. BMC Microbiology, 24(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-024-03425-y

Molodecky, N. A., Soon, I. S., Rabi, D. M., Ghali, W. A., Ferris, M., Chernoff, G., Benchimol, E. I., Panaccione, R., Ghosh, S., Barkema, H. W., & Kaplan, G. G. (2012). Increasing Incidence and Prevalence of the Inflammatory Bowel Diseases With Time, Based on Systematic Review. Gastroenterology, 142(1), 46-54.e42. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001

Schirmer, M., Garner, A., Vlamakis, H. et al. Microbial genes and pathways in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 17, 497–511 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-019-0213-6

Ulcerative Colitis vs Crohn’s Disease. (n.d.). UCLA Health. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://www.uclahealth.org/medical-services/gastro/ibd/patient-resources/ulcerative-colitis-vs-crohns-disease

Wu, H. J., & Wu, E. (2012). The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes, 3(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.4161/gmic.19320

Xiang, W., Xiang, H., Wang, J., Jiang, Y., Pan, C., Ji, B., & Zhang, A. (2023). Fecal microbiota transplantation: A novel strategy for treating Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Microbiology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1281233