Background:

The industrialization of the food industry has undergone a dramatic transformation in recent years. The average western consumer now consumes more ultra-processed food than ever before, shifting away from more seasonal and traditional diets. This change is being fueled by the advancement in marketing techniques, which shows over 50 percent of all food and beverage advertisements are processed foods (Zhang et al. 2022), and making ultra-processed food more readily available and appealing. However, this convenience comes at a cost: rising rates of obesity, heart disease, and diabetes are at an all time high in Western populations (Rakhra et al. 2020).

The relationship between diet, health, and our microbiome is becoming increasingly clear as more studies are conducted. Diets that are high in unhealthy fats and sugars lead the gut microbial population to decrease (Townsend et al. 2018), which can reduce the overall health of the host. An unhealthy microbiome could lead to inflammation, obesity, diabetes, and even cancer (Zhang et al. 2015). However, most of the research and understanding of the gut microbiomes focuses on western industrialized populations. This leaves significant gaps of knowledge for those populations who are in non industrialized regions, and possibly leaves a wealth of microbes undiscovered.

As research continues to dive deeper into the implications of ultra-processed foods, we must understand that our food choices have major impacts on our gut microbiome. Immigrants who move to the United States often see dramatic shifts in their gut microbiome, supporting a link that food choice plays a major role in gut microbiome (Carter et al. 2023). Addressing these issues requires an approach that includes research of diverse populations whose food consumption differs from industrialized populations. By gaining this information we would be able to bridge the gaps in our knowledge, and better navigate the complexities of the gut microbiome. The research that will be shared in this blog post comes from a Carter et al. paper from 2023 titled “Ultra-deep sequencing of Hadza hunter-gatherers recovers vanishing gut microbes” (Carter et al. 2023) and helps us start to fill our knowledge gap.

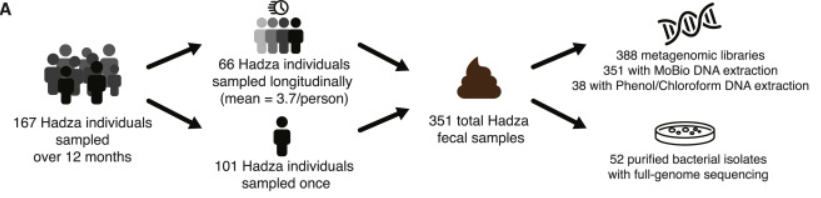

Figure 1. This conveys the total number of Hadza samples that were taken and how they were sampled. This comes from Carter et al. 2023 Figure 1 A.

Central question:

Do populations who eat non industrialized foods have different gut microbiomes than the western industrialized populations?

Findings:

The Hadza tribe in Africa made for the perfect sample group as they are one of the few populations left without the introduction of any kind of processed foods and modern medicine. During a year-long study the tribe provided fecal samples which were used in DNA analysis to discover the gut microbes that were present. Additional populations were sampled from California and Nepal to help provide the study with a better understanding of how the gut microbiome is changing. To do this, they used DNA sequencing (this process allows researchers to look at the genes and organisms present in the sample). From this over 90,000 genomes were found from the Hadza group with 44% of them absent from any existing database.

This study is the largest of its kind, which looks more in depth at what is really in the gut. Previous studies of even industrialized populations only use a type of targeted sequencing method that helps identify the collection of microbes in the sample.

The results showed that 48,475 bacterial and archaeal, 17 eukaryote, and 34,552 bacteriophage genomes were recovered from DNA extractions. Anaerobic cultivation was done on the stool samples as well which recovered 52 more bacterial strains which all underwent full genome sequencing. The genomes belonged to 31 bacterial strains which revealed that 18 of them had never been previously cultivated and 9 which were not present in the Unified Human Gastrointestinal genome database.

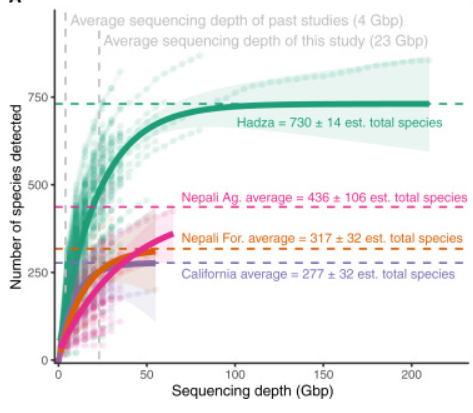

Analysis revealed that the average gut microbiome in a Hadza adult contains around 730 species. This number is much higher than the average adult in California and Nepal (Fig. 2). The next closest average was the Nepal agrarians gut microbiome with only an average of 436 species. The differences in these averages are statistically significant and show that the Hadza people have a different composition in their gut microbiome with a much higher diversity in bacteria, bacteriophage, and archaea.

Figure 2. This compares the average number of species in the different population samples. This comes from Carter et al. 2023 Figure 3 A.

Future Research:

Researchers acknowledged that the main limitation to their study was that there was only one group of hunter-gatherers that was studied. However while this was a limitation this is a great step in the right direction for future studies to look at other groups of hunter-gatherers before starvation and land loss lead these tribes to become industrialized.

With this data there are future questions and research that could be presented to try and reverse the loss of gut microbes occurring in western populations. The first question is trying to find out why these microbes were selected out of the western population to begin with. We know that ultra-processed foods lower microbiome diversity (Sierra et al. 2021) but is there a chance we no longer need these microbes with access to modern medicine or does food sanitation kill off the good bacteria as well? Once a complete database of microbes that were selected out of the western population is completed, finding out why they are not present could be critical to maintaining a healthy population.

Once this is complete, finding out whether or not we can reintroduce some of these microbes to try and help improve our well being may be the key to solving some of the health issues in western culture. The researchers in Lawrence et al. have already discovered that restoring the microbiome with the use of probiotics and prebiotics can improve digestion and emotional well being (Lawrence et al. 2018). Which furthers the question if these microbes were reintroduced to western populations would there be a health increase.

Further reading:

The gut microbiome is important in your overall health and well being. It can affect more than just your gut and can even increase your risk for cancer. This paper discusses the role the gut microbiome has on one of the most diagnosed types of cancer.

The consumption of ultra-processed food is increasing while the consumption of fresh non processed foods are on the decline throughout western populations. This paper discusses the differences that these foods are having on Spanish populations.

How ultra-processed foods are marketed and the strategies used to get consumers to buy them are not well known. This paper starts to break down how the food industry markets ultra-processed foods, focused in the United States.

References:

Ağagündüz, D., Cocozza, E., Cemali, Ö., Bayazıt, A. D., Nanì, M. F., Cerqua, I., Morgillo, F., Saygılı, S. K., Berni Canani, R., Amero, P., & Capasso, R. (2023). Understanding the role of the gut microbiome in gastrointestinal cancer: A Review. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1130562

Carter, M. M., Olm, M. R., Merrill, B. D., Dahan, D., Tripathi, S., Spencer, S. P., Yu, F. B., Jain, S., Neff, N., Jha, A. R., Sonnenburg, E. D., & Sonnenburg, J. L. (2023). Ultra-deep sequencing of Hadza hunter-gatherers recovers vanishing gut microbes. Cell, 186(14). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.05.046

Sierra, A., Milagro, F. I., Aranaz, P., Martínez, J. A., & Riezu-Boj, J. I. (2021). Gut microbiota differences according to ultra-processed food consumption in a Spanish population. Nutrients, 13(8), 2710. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082710

Lawrence, K., & Hyde, J. (2017). Microbiome restoration diet improves digestion, cognition and physical and emotional wellbeing. PLOS ONE, 12(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179017

Rakhra, V., Galappaththy, S. L., Bulchandani, S., & Cabandugama, P. K. (2020). Obesity and the western diet: How we got here. Missouri medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7721435/

Townsend, G. E., Han, W., Schwalm, N. D., Raghavan, V., Barry, N. A., Goodman, A. L., & Groisman, E. A. (2018). Dietary sugar silences a colonization factor in a mammalian gut symbiont. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(1), 233–238. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813780115

Zhang, Y.-J., Li, S., Gan, R.-Y., Zhou, T., Xu, D.-P., & Li, H.-B. (2015). Impacts of gut bacteria on human health and diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16(4), 7493–7519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16047493Zhong, A., Kenney, E. L., Dai, J., Soto, M. J., & Bleich, S. N. (2022). The marketing of ultra processed foods in a national sample of U.S. supermarket circulars: A pilot study. AJPM Focus, 1(1), 100009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focus.2022.100009