Image: example of mother bottle feeding infant (captured by Anna Stills)

Background

The first few months of an infant’s life are very important for the development of the gut microbiota, which shapes immune responses, metabolic function, and overall health. The gut microbiota is a complex community of tiny microbes that inhabit your digestive system, namely the large intestine. Early colonization of the gut can change based on factors like how a baby was born (vaginal vs cesarean section), what they eat (breastfeeding vs formula) and healthcare treatments (antibiotic use). Disruptions to this delicate balance during infancy can have long-term consequences like increasing the risk for certain conditions like allergies, obesity and gastrointestinal disorders later in life (Lagouvardos, 2022, p.334).

Given the deep connection between the gut microbiota and health, scientists are looking into how different decisions during infancy can shape these microbial communities. One of these decisions is the use of synbiotics. Synbiotics are a combination of probiotics (live beneficial bacteria) and prebiotics ( food for bacteria). Synbiotic formulas, which blend probiotcs and prebiotics, are made to copy the benefits of breastfeeding and support the development of a healthy gut microbiome in infants who are not breastfed. Synbiotic formulas are common but are, not surprisingly, more expensive than their non-synbiotic formula counterparts.

A study by Lagouvardos et. al, completed in 2023 explores the impact of synbiotic formula on the gut microbiota of infants. This study tries to address how the use of synbiotic formula during the two years of life influences the development of a healthy gut microbiota in infants, possibly offering health benefits close to the benefits of breastfed infants.

Central Question

The central question of Lagouvardos et al. 2023 research is whether infants who consume a synbiotic formula develop a gut microbiota composition that is more beneficial in terms of microbial diversity and the presence of key bacteria associated with long-term health outcomes, compared to those who consume a standard formula without synbiotics as well as those who are breastfed.

Evidence

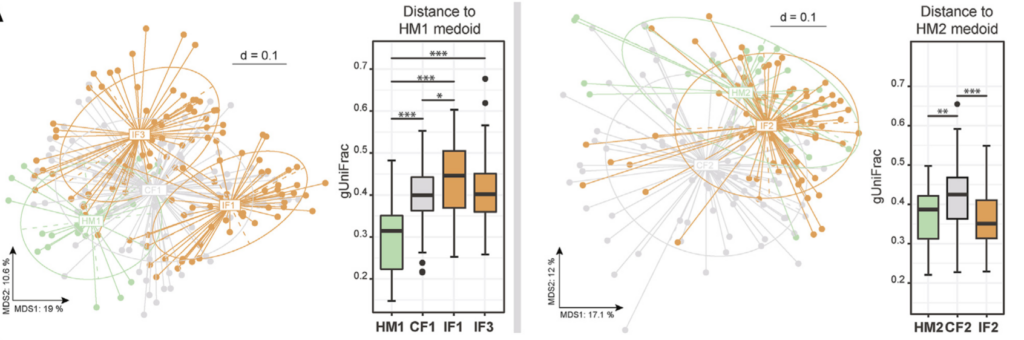

Figure 6. (A) uses a MDS plot to show the similarities in the gut bacteria of infants who were fed different formulas and those who were breastfed. It shows that infants fed a special formula (called IF) had gut bacteria that were more similar to breastfed infants, specifically in a group of infants with a lower amount of Bacteroides spp. bacteria; (Lagouvardos et al. 2023)

To explore the effects of synbiotic formula on the gut microbiota of infants, the researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial involving European infants. Infants were randomly assigned to receive either a synbiotic formula or a standard formula without synbiotics. The trial followed a double-blind set up, meaning that neither the parents or the researchers knew which formula each infant was receiving. This approach helped eliminate the possibility of any bias, and ensured that the results were driven purely by the effects of the formula itself

Over the course of the study, stool samples were collected from the infants at different stages- before, during, and after the formula was given. The samples were then analyzed using a genetic marker specific to bacteria to identify and quantify the bacterial species present in the gut. By comparing the microbiota profiles of infants in the synbiotic group to those in the standard formula group, the researchers were able to assess the impact of the synbiotic formula on the gut microbial community.

The study’s findings showed significant differences in the gut microbiota between infants who received the synbiotic formula and those who received the standard formula. One of the most noteworthy outcomes was the increased presence of Bifidobacterium species in the synbiotic group. Bifidobacterium is a group of bacteria that plays a key role in early life gut health, because it aids in the digestion of human milk oligosaccharides (also known as HMOs) in breast milk, supports immune development, and protects against harmful pathogens. The synbiotic formula was shown to promote higher relative abundance of Bifidobacterium (Lagouvardos, 2022, p.334), aligning the microbiota profile of the formula-fed infants more closely with that of breastfed infants, who typically have higher levels of this beneficial bacteria.

In addition, the infants in the symbiotic group exhibited greater microbial diversity, which is generally considered a marker of a healthy gut microbiome (Grace-Farfaglia et al, 2022). A diverse gut microbiota is better equipped to handle various environmental stressors and is associated with a reduced risk of diseases like allergies, obesity, and autoimmune conditions. In contrast, infants in the standard formula group had lower microbial diversity and fewer Bifidobacterium species, which could suggest a less robust gut microbiome.

Furthermore, the study also revealed that the effects of the synbiotic formula varied depending on the initial gut microbiota composition of each infant. Infants who started with a less mature or less diverse microbiota appeared to benefit the most from the synbiotic intervention. In other words, infants with less diverse gut microbiota gained more from synbiotic formula with increased presence from beneficial bacteria, like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, increasinging the overall diversity of their microbiota. This is important since the gut microbiome can influence immunological, endocrine and neural pathways in infants (Yang et. al, 2016). This suggests that the synbiotic formulas may be beneficial for infants born via cesarean section or those who receive antibiotics early in life, seeing as these are known factors that disrupt the development of a healthy gut microbiota.

My Questions

This study provides compelling evidence that synbiotic formulas can help support the gut microbiota for formula fed infants, however it also raises several questions that warrant further investigation. For example, one question I had was about the duration of the effects of the synbiotic formula. The study only followed infants during the initial months of life, but it was unclear whether the beneficial changes in the gut microbiota persist into childhood or if the microbiota eventually reverts to a composition similar to a standard formula-fed infant. Long-term studies tracking the health and microbiome composition of children who received synbiotic formulas would be valuable in addressing my question and also adding to the previous research article.

Another question I had was whether specific strains of probiotics and types of prebiotics used in the synbiotic formula are optimal for promoting gut health. This study focused on a particular synbiotic formulation, but different combinations of probiotics and prebiotics might have varying effects on the gut microbiota. Future research could explore which probiotic strains and prebiotic compounds are most effective at promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium and enhancing microbial diversity.

Moreover, I also think it would be worthwhile to investigate how synbiotic formulas affect other aspects of infant health beyond the gut microbiota. While the study primarily focused on microbial changes, future research could examine whether synbiotic formulas reduce the incidence of infections, allergies or gastrointestinal issues in infants. These outcomes would provide further evidence for the potential health benefits of synbiotic formulas and help guide recommendations for their use.

Lastly, given that the initial gut microbiota composition influenced how infants responded to the synbiotic formulas, personalized nutrition strategies might be the next step. Maybe testing an infant’s gut microbiota at birth can help identify those who would most benefit from synbiotic formulas. Tailoring infant nutrition based on microbiome profiles could maximize the effectiveness of interventions like synbiotics and support optimal gut health in early life.

Further Reading and Information

Youtube: Microbiome and Development https://youtu.be/eL9dAGiCNLU

Youtube: Your Baby’s Gut Microbiome | GutDr Mini-Explainer https://youtu.be/y5MBS9ZQfiA?si=WyZ4jYC5V6hHFo5p

Microbiome Overview Explained:

Suggestions on How to Support Your Child’s Microbiome: https://www.tinyhealth.com/blog/the-infant-microbiome-4-tips-to-support-baby-gut-health

Phases of Microbiome Development in Children: https://www.mothersbabies.org/the-phases-of-development-of-the-gut-microbiome-in-babies-and-children-4/?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwgrO4BhC2ARIsAKQ7zUl8NKXqzzep_OBPhWvnNNY-U8Xyy4CU4_bT3jEnlcR9_vH27q9UM1IaArm9EALw_wcB

References

Bäckhed, F., Roswall, J., Peng, Y., Feng, Q., Jia, H., Kovatcheva-Datchary, P., … & Wang, J. (2015). Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell host & microbe, 17(5), 690-703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004

Grace-Farfaglia, P., Frazier, H., & Iversen, M. D. (2022). Essential factors for a healthy microbiome: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8361. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148361

Granger, C. L., Embleton, N. D., Palmer, J. M., Lamb, C. A., Berrington, J. E., & Stewart, C. J. (2021). Maternal breastmilk, infant gut microbiome and the impact on preterm infant health. Acta Paediatrica, 110(2), 450-457 https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15534https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15534

Mueller, N. T., Bakacs, E., Combellick, J., Grigoryan, Z., & Dominguez-Bello, M. G. (2015). The infant microbiome development: mom matters. Trends in molecular medicine, 21(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2014.12.002

Quin, C., Estaki, M., Vollman, D. M., Barnett, J. A., Gill, S. K., & Gibson, D. L. (2018). Probiotic supplementation and associated infant gut microbiome and health: a cautionary retrospective clinical comparison. Scientific reports, 8(1), 8283. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26423-3

Turroni, F., Milani, C., Duranti, S., Lugli, G. A., Bernasconi, S., Margolles, A., … & Ventura, M. (2020). The infant gut microbiome as a microbial organ influencing host well-being. Italian journal of pediatrics, 46, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-020-0781-0

Yang, I., Corwin, E. J., Brennan, P. A., Jordan, S., Murphy, J. R., & Dunlop, A. (2016). The Infant Microbiome: Implications for Infant Health and Neurocognitive Development. Nursing research, 65(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000133

Yassour, M., Vatanen, T., Siljander, H., Hämäläinen, A. M., Härkönen, T., Ryhänen, S. J., Franzosa, E. A., Vlamakis, H., Huttenhower, C., Gevers, D., Lander, E. S., Knip, M., DIABIMMUNE Study Group, & Xavier, R. J. (2016). Natural history of the infant gut microbiome and impact of antibiotic treatment on bacterial strain diversity and stability. Science translational medicine, 8(343), 343ra81. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0917