Musicians alike, from Roy Orbison and Gram Parsons to Rod Stewart and classic rockers Nazareth have crooned woefully on that most powerful of feelings: Love hurts. Each of these fellas, though, had at least one thing going for him. Although they may have been jilted by former lovers, they can be thankful that none of them was a praying mantis! Scientists (and Tina Turner) may rightly question What’s love got to do with it? But there can be no doubt, mantis mating can be a very painful experience for the males involved. That’s because female predatory mantises practice sexual cannibalism, or the act of consuming a male mate before, during, or following a reproductive event. As many as one in four mantis sexual encounters may involve cannibalistic behavior. And while this bit of trivia knowledge has been known for quite some time now, two questions have continued to perplex evolutionary biologists:

How did sexual cannibalism evolve and why has it persisted in the face of natural selection?

In the insect world, a male will often court his mate with resources beyond just the sperm needed to fertilize her eggs. These resources are termed nuptial gifts and may take the form of food items or simple decorative trinkets. Elaborate gifts combine nutriment with reproductive material. For example, males of some species provide additional nutrients for the female via a small packet known as a spermatophore. The spermatophore contains spermatozoa that are used for fertilization in addition to a protein-rich supplement which can be eaten by the female. More competitive males provide more lavish nuptial gifts. Do male mantises offer themselves up as the ultimate nuptial gift? Or does the female not allow him a choice in the matter?

There are several hypotheses out there which attempt to explain why sexual cannibalism evolved in the first place (see the links at the end of this post for more about these different theories). A study published earlier this year in the academic journal Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B may help to explain why natural selection has not yet snuffed out such a seemingly self-destructive behavior. Natural selection works by favoring physical traits and behaviors which increase the “fitness’ of individuals in a population. This helps to perpetuate the species and gives rise to the phrase “survival of the fittest.’ It would seem natural, then, that a behavior which results in the death of a quarter of male mantises following a single reproductive event would quickly be eliminated. Numbers don’t lie: for every female mantis who eats her mate, there is one less male in the breeding population. After all, while certain spider species that practice sexual cannibalism lack the ability to mate more than once, male mantises that survive a sexual encounter can mate again. So, what is the evolutionary advantage of this striking behavior?

Evolutionary biologists define fitness as an individual’s lifetime contribution of offspring to the next generation. This definition encompasses aspects of both survival and reproductive success. So, evolutionarily speaking, an individual is considered “unfit’ if it fails to produce offspring. In other words, all that exercise and dieting is for naught if you don’t have children! With this in mind, the authors hypothesize that sexually cannibalistic behavior will be selected for only if the nutrition gained from consuming her mate increases the female mantis’s survival and the number of eggs sired by the sacrificed male. Furthermore, the increase in the number of eggs sired would have to be so great as to offset the cost of preventing the male from surviving and going on to reproduce again. Only in this way can both the male and female benefit from sexual cannibalism.

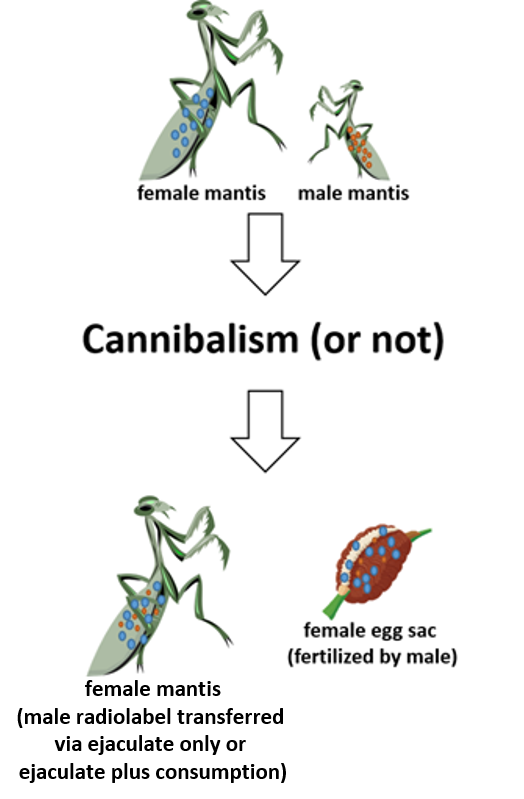

The authors designed and conducted a simple experiment to determine if male sacrifice does, in fact, lead to higher reproductive success for both sexes. Such a finding would provide evidence for a selective advantage to sexual cannibalism. Praying mantises were fed crickets with radioactive markers for carbon and hydrogen in their amino acids (henceforth called radiolabels). Upon consuming their prey, these radiolabels become incorporated into the cells of the mantises. Different radiolabels were used for males and females. Male and female mantises were then placed in plastic containers and allowed to mate. Cannibalism before and during sex was prevented in all cases. Following copulation, the researchers left half of the pairs confined together until the female consumed the male. The other half were separated immediately following copulation. The first egg sac deposited by each female was not considered in this study. This allowed her more time to digest her mate and reduced the possibility of the researchers analyzing eggs that were fertilized by a previous mate. The researchers took three radiolabel measurements starting with the second egg sac deposited. First they recorded the proportion of the total male radiolabel that was incorporated into the female mantis’s body. Next, the researchers measured the proportion of the total (male and female) radiolabel in the female’s reproductive tissues and eggs that was derived from the male. The final measurement recorded the proportion of the male radiolabel that was incorporated into the female’s body vs. reproductive tissues/eggs. Additionally, the total number of eggs was counted for each female (excluding the first egg sac and including eggs remaining in the ovaries).

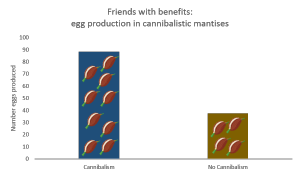

Luckily for the male mantis, his sacrifice is not made in vain! The results show that a female mantis incorporates significantly more male radiolabels into her body when she consumes her mate than when he is allowed to survive. This may seem intuitive, and not very beneficial to the male. The results also show, however, that significantly more male radiolabels are incorporated into the female’s reproductive tissues and eggs as a result of sexual cannibalism, meaning the male’s sacrifice is making a direct contribution to his offspring. Females assimilate male radiolabel similarly, allocating between 66-75% of the nutriment to the offspring regardless of whether the radiolabels are obtained from the ejaculate or directly from consuming his body. Perhaps most importantly, cannibalistic females produced significantly more eggs following the first egg sac than their non-cannibalistic counterparts. So, not only does the male’s sacrifice provide his mate and offspring with a significant source of nutrition, he also bolsters the number of offspring that he sires, thereby improving his own fitness. Talk about extreme parental care!

With the benefits of male sacrifice confirmed and quantified, the last remaining question is under what natural conditions is this behavior more beneficial than male survival? It might be better for the male to survive if he had a good chance of mating with several more females. On the other hand, the authors suggest that sexual cannibalism may be an adaptive strategy for the male when those chances are slim (is a life without sex really a life worth living?). This could occur in nature if the chances of finding more than one female were extremely low, if there were many more males than females in the population, or if overall population numbers were very low. However, the authors fail to consider how the male’s sacrificial benefit will be impacted if the female manages to mate with a second male (and possibly cannibalize him) before laying her eggs. Will the first male still have increased parenthood, or will that honor be bestowed upon the second mate? Even more complicated questions arise if we consider that whether the male benefits in this way may be an irrelevant point. Could this behavior in other species be driven by nothing more than female hunger? Is the one in four odds of becoming a meal worth the risk? If so, then why have males not evolved an escape mechanism, thus driving an evolutionary arms race between the sexes? Further studies might benefit from looking at what, if any, factors determine when sexual cannibalism occurs in the wild. Comparisons with other mantises and spiders known to display sexual cannibalism could also lead to more insights, as would studies of reproductive success in mantises that do not engage in cannibalistic behavior. One thing seems certain: men will put up with almost anything for sex! Fortunately, sexual cannibalism is only known to be practiced by invertebrate animals, so listen up, fellas! Pay no attention to Mr. Hall and Mr. Oates – no matter how difficult your darling girl can be, she’s no Maneater!

Further Reading

Several scientific hypotheses attempt to explain the evolution of sexual cannibalism. The adaptive foraging hypothesis is detailed here. A cruel form of mate choice is posited here. And, finally, the aggressive spillover hypothesis can be explored here.

For more on sexual cannibalism in wild mantises, see this study which explores the ecological and phylogenetic conditions that may predispose mantises to cannibalism. Or, check out this study which examines the biology, mating behavior, and frequency of sexual cannibalism in a wild population of mantises in Portugal.

Finally, LiveScience describes a similar study of orb-web spiders here.

References: Barry, Katherine L., Gregory I. Holwell, and Marie E. Herberstein. "Female praying mantids use sexual cannibalism as a foraging strategy to increase fecundity." Behavioral Ecology 19.4 (2008): 710-715. Brown, William D., and Katherine L. Barry. "Sexual cannibalism increases male material investment in offspring: quantifying terminal reproductive effort in a praying mantis." Proc. R. Soc. B. Vol. 283. No. 1833. The Royal Society, 2016. Johnson, J. Chadwick. "Sexual cannibalism in fishing spiders (Dolomedes triton): an evaluation of two explanations for female aggression towards potential mates." Animal Behaviour 61.5 (2001): 905-914. Kralj-Fišer, Simona, et al. "Mate quality, not aggressive spillover, explains sexual cannibalism in a size-dimorphic spider." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 66.1 (2012): 145-151. Lawrence, S. E. "Sexual cannibalism in the praying mantid, Mantis religiosa: a field study." Animal Behaviour 43.4 (1992): 569-583. Wilder, Shawn M., Ann L. Rypstra, and Mark A. Elgar. "The importance of ecological and phylogenetic conditions for the occurrence and frequency of sexual cannibalism." Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 40 (2009): 21-39.