Background:

Sleep disorders can have a major impact on health, and when sleep cycles are disturbed this can increase the risk of additional disorders such as cardiovascular diseases or obesity. ‘Sleep disorder’ is a vast term that can be applied to anything from sleep quality to length of time spent asleep, and can include a variety of disorders such as sleep apnea, narcolepsy, restless legs syndrome, and predominantly insomnia. Insomnia is a disorder where individuals have trouble falling asleep, or staying awake and also focuses on quality of sleep. Insomnia doesn’t stem from a single source in the human body. It has many unknown factors contributing to its condition. So, one of the best ways to move forward in helping treat insomnia is by looking at the various aspects of the body that contribute to it, starting with the human microbiome.

Some factors particularly of interest are changes in relationships between groups of bacteria found in the guts of insomniacs and normal individuals, particularly between Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (F and B). Firmicutes are a phylum of gut bacteria that help break down carbohydrates such as fiber and starch as well as release butyrate which is short chain fatty acid that helps prevent inflammation (Edermaniger, 2021). Bacteriodetes release butyrate and help with bile acid metabolism (Thomas et al 2011). This ratio of F/B not only changes between individuals with insomnia and those without, it also has been found to change between healthy individuals and those with additional disorders, like obesity or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In a study examining the effects of probiotics on the F/B ratio, it was found that an increase in the F/B ratio correlated with obesity, while decreases in the F/B ratio correlated with IBD (Stojanov et al 2020). This importance of the F/B ratio is crucial in understanding how to treat disorders like insomnia, and a recent study by Liu et al (2019) provides a valuable step forward.

Central questions:

How do the gut microbiomes of individuals with insomnia and healthy individuals differ? Can we pinpoint certain microbes that are more prevalent in individuals with insomnia?

Evidence:

The study by Liu et al (2019) used 20 individual volunteers from Guangzhou, China, who were split into two groups-insomnia and a control group. The individuals were assessed using preset standards such as an age between 18 and 60 and no other mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder (as these might cause confounding variable differences in microbiota). By comparing the species richness, or the number of different microbiota species present, between healthy individuals and individuals with insomnia, this study (Liu et al 2019) discovered that the gut microbiota differed significantly.

To start, the study found a significant difference between the α- and β-diversity of the gut microbiota of individuals with insomnia and the control group. Alpha diversity (α) measures the variation of microbiota within one subject, while Beta diversity (β) measures the differences between the microbiota of multiple subjects. The significant difference in beta diversity between groups illustrates how there is a measurable difference between the gut microbiota of healthy individuals and those with insomnia, which supports the goal of this study.

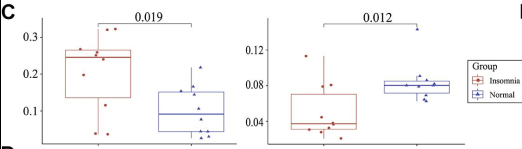

Three groups of interest included the Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes phyla, with the Bacteroidetes being the most prominent taxa in the individuals with insomnia. Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes form a ratio in the gut seen throughout this study. The F/B ratio in the gut has been shown to indicate changes in the gut microbiome, or dysbiosis, with increases or decreases in the ratio being correlated with disorders like obesity or IBD (Stojanov, 2020). In this study, since the Bacteroidetes were dominant in the gut microbiomes of insomnia individuals, it resulted in a decreased ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F/B) from the control group (Fig 4c). While this discrepancy was significant in this study, previous studies showed no change in the ratio of F/B between insomnia individuals and controls (Benedict et al 2016). An explanation for the significant difference present in this study could be that the individuals with “insomnia” don’t really have the disease, rather they have sleep restrictions and deprivation of sleep, so this could promote differences not seen in true individuals with insomnia. Since the individuals in the study don’t truly have the insomnia disease, this could impact the results seen because of altered gut microbiomes from individuals who do have insomnia. This altered ratio, however, is seen in other individuals with diseases like type II diabetes (Larsen et al 2010), so it isn’t a far stretch to predict this altered F/B ratio may be indicative of issues such as insomnia.

Not only was the physical composition of the gut microbiome, particularly the F/B ratio, different between individuals with insomnia and the control group, certain metabolic pathways differed as well. Considering the F/B ratio, insomnia individuals had higher levels of Bacteroidetes as compared to Firmicutes than the individuals in the control (Fig 1). This study utilized a software that predicted abundances in a community, called PICRUST 2, and using this software they found that individuals in the insomnia group were predicted to have an enriched Vitamin B6 metabolism, as well as enriched steroid hormone biosynthesis, retinol metabolism, folate biosynthesis, and the citrate cycle.

This would indicate that different metabolism and biosynthesis pathways were used between individuals with insomnia and the control group. This is significant because different pathways lead to different results in the body. For example, an enriched Vitamin B6 metabolism means that individuals with insomnia utilize Vitamin B6 a lot faster than those in the control group, which leaves a deficit of Vitamin B6 in the body. This can lead to other issues, such as sleep disturbances (Djokic et al. 2019). Expanding on the systematic complexity of the gut bacteria in individuals with insomnia, the study found that the system complexity didn’t change significantly. This indicates that the gut microbiota of insomnia individuals is well established in the gut, meaning these bacteria aren’t just “coming and going”-they are actively interacting in the gut microbiome. After analysis of the data found in this study, it is still unclear whether insomnia is the cause of the altered gut microbiome, or if it is the other way around. This is important because we have yet to determine whether we should treat the gut microbiome first in order to help with insomnia symptoms, or if there are additional problems causing insomnia that are affecting the gut microbiome. Ultimately, though this study had a small sample size, it did well in creating a first step towards examining the relationship between the insomnia disorder and the gut microbiome.

My questions:

What, if any, environmental factors such as diet contribute to the formation of the gut microbiome seen in individuals with insomnia? Are these environmental factors also found in studies with the corresponding disorders of insomnia, like obesity or cardiovascular disorders? Looking at parameters of the study, how might the gut composition between insomnia and healthy individuals change with a larger sample size greater than simply twenty individuals? Continuing this, how might the gut composition change if the test subjects labeled “insomnia” actually had the insomnia disorder, rather than controlled sleep deprivation to mimic the disorder?

Further reading:

- An author video on a previous study done on the gut microbiota in response to sleep deprivation. Researchers J Cedernaes and C Benedict discuss their paper and research on the relationship of sleep deprivation and the development of metabolic disorders. They specifically examine how the F/B ratio is altered by sleep deprivation.

- A discussion of insomnia from sleep medical specialists Rachel Salas (M.D) and Virginia Runko (Ph.D). These specialists explain the insomnia disorder, and examine some causes and risks for developing the disorder. This video is hosted by the John Hopkins Sleep Center in the Howard County General Hospital.

- Findings of a study similar in nature in that they compare the gut microbiota between healthy individuals and individuals with a disorder (in this case type II diabetes)

- A blog describing the role of Firmicutes in the gut by Leanne Edermaniger, a science blogger and writer from the UK. Edermaniger has written 95 and counting articles specifically focused in microbiome science.

References:

Benedict, C., Vogel, H., Jonas, W., Woting, A., Blaut, M., Schürmann, A., & Cedernaes, J. (2016, October 24). Gut microbiota and glucometabolic alterations in response to recurrent partial sleep deprivation in normal-weight young individuals. Molecular Metabolism 5(12) 1175-1186 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2016.10.003

Cedernaes, J., & Benedict, C. (Directors). (2017, January). Author Video [Video file]. Retrieved from https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S2212877816301934-mmc2.mp4

Djokic, G., Vojvodić, P., Korcok, D., Agic, A., Rankovic, A., Djordjevic, V., . . . Lotti, T. (2019, August 30). The Effects of Magnesium – Melatonin – Vit B Complex Supplementation in Treatment of Insomnia. Open Access 7(18) 3101-3105 PMC: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6910806/

Edermaniger, L. (2021, June 21). Firmicutes Bacteria: What Are They And Why Are They Important? Retrieved from https://atlasbiomed.com/blog/guide-to-firmicutes/

HopkinsHowardC. (2013, October 22). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_tXFhGRqggc&t=213s

Larsen N, Vogensen FK, van den Berg FWJ, Nielsen DS, Andreasen AS, Pedersen BK, et al. (2010) Gut Microbiota in Human Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Differs from Non-Diabetic Adults. PLoS ONE 5(2): e9085. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009085

Liu B, Lin W, Chen S, Xiang T, Yang Y, Yin Y, Xu G, Liu Z, Liu L, Pan J and Xie L (2019) Gut Microbiota as an Objective Measurement for Auxiliary Diagnosis of Insomnia Disorder. Front. Microbiol. 10:1770. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01770

Poroyko, V. A. et al. (2016) Chronic Sleep Disruption Alters Gut Microbiota, Induces Systemic and Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 35405; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35405

Stojanov, S., Berlec, A., & Štrukelj, B. (2020, November 01). The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease. Microorganisms 8(11) 1715 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8111715

Thomas F, Hehemann J-H, Rebuffet E, Czjzek M and Michel G (2011) Environmental and gut Bacteroidetes: the food connection. Front. Microbio. 2:93. DOI: doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2011.00093