The vaginal microbiome: We live in a world of microbes, and yet we are still learning new things about these millions of ‘germs’ every day and how they influence us, but what about our children? New research suggests a mother’s stress during pregnancy could be another puzzle piece in the development of baby’s microbiome and brain. According to the CDC nearly 4 million children were born in the United States in 2016, which resulted in mothers giving their offspring microbes, whether the baby was born through c-section or vaginally. Recent research (Rutayisire et al., 2016) is starting to show that there may be an advantage to birthing vaginally, as young are exposed to their mother’s microbiome.

Within the last decade, research (Tamburini et al., 2016) has shed new light on the microbiome of young infants and health implications later in life. Eldin Jasarevic is a post doc at the University of Pennsylvania, and much of his research focuses on the connection between the gut microbiome and the brain axis in relation to health and disease. Jasarevic began his studies on the vaginal microbiome and how it affects the health of mouse offspring. He first found that there were changes in the vaginal microbiome caused by maternal stress (Jasarevic et al., 2014) and linked it to changes in the offspring’s gut microbiome and brain. In his newest study, Jasarevic et al. (2018) found that a mother’s stress during pregnancy may specifically influence the hypothalamus, the part of the brain that controls important body functions such as body temperature, sleep cycle, hunger, and thirst.

To find a more specific cause, Jasarevic designed a new experiment to look at the the response of the hypothalamus, which responds to stress by sending signals to the pituitary gland and the adrenal medulla. A stress response generally causes an increased heart rate, increased breathing, and suppressed digestive activity (Wikipedia, 2018). Long term stress is regulated by hypothalamic pituitary adrenal system, ultimately producing corticosteroid which allows the body to maintain a steady supply of blood sugar which helps people (and animals) to cope with the long term stressor and later helps the body to return to normal functions. During a time of stress, the immune system is suppressed in the body.

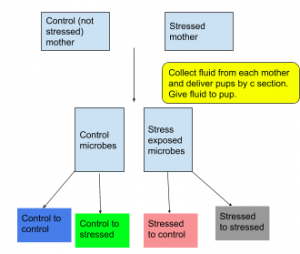

This means that offspring may only benefit somewhat from their mother’s microbiome, and perhaps only if she is unstressed during pregnancy. Other potential factors include the birth method, as vaginal microbes may be more beneficial than a c section. In his experiment, Jasarevic uses all c section born mice in order to control for the type of vaginal microbiome the pups are exposed to, either stressed or unstressed mothers.

Central question:

What are the effects of a stressed mother’s changing vaginal microbial community during pregnancy on her offspring’s microbiome and brain?

What did he find?

The authors then looked into the specific types of bacteria present in the mice pup’s gut microbiome, and were able to find differences in the abundance of E. coli, Streptococcus acidominimus and Peptococcaceae when looking between the stressed exposed mother’s offspring and control mother’s offspring. These bacteria are important for the mucus immunity and building of metabolism in the young. This means the pups who were exposed to the microbe community might have a weakened immune system and long term effects from the exposure to the mother’s microbes.

To examine the effects of the maternal stress on the offspring’s brain development, the researchers looked at the hypothalamus specifically, using corticosterone (stress hormone) levels as a marker. Following the figure 1, they were particularly interested in C-S and S-C mice, using C-C and S-S as two controls of the stress levels they would expect in the mice normally born. They found that C-C (control to control, blue on figure) mice were calmer than S-S (stressed to stressed, grey on figure) mice, and that the S-C (stressed to control, pink on figure) hormone levels sat at a kind of intermediate between the two, which suggested the mother’s microbiome might influence the stress hormone response. The C-S group (green on figure) would ideally have acted as a ‘restoration’ where the researchers would expect to see some kind of recovery from the administration of control fluid, but surprisingly they did not. They also found that there was an increase in S. lentus, a species of bacteria involved in inflammation, between stressed control and unstressed control. Authors also observed a decrease in L. reuteri, a species that helps the body to maintain its barriers (skin, mucus membrane, intestines, etc.).

I would propose further studies using mice, looking at ways to counteract or reverse the ‘damage’ we see by the prenatal stress, possibly by reintroducing the normal “good’ bacteria at different stages of the mouse’s life. Past studies done by Jasarevic showed that they were able to somewhat restore the microbiome of young mice. His team proposed that there may be a window of time in which they would be able to restore the microbiome, but they are not sure of the cut off.

Questions for the future:

- Does this ‘restoring microbiome’ have the potential to be applied to humans? This would give us a way to potentially look at infants born by c-section and find a way to ensure that they also receive the same benefits of the vaginal microbiome from their mothers.

- Why are only male mice affected? What might this suggest about females that makes them unaffected? If we can figure out why the females are unaffected, it may shed light on what we humans can do so that our own children are not affected by our stress during pregnancy.

- Is this study itself significant? Or does it simply provide a stepping stone to finding a greater impact? To me, this study follows its published pilot study (Jasarevic et al. 2015) and helps us to narrow in on a connection between the maternal microbiome and offspring’s gut microbiome and stress response, but that seems to only provide another stepping stone. It is significant because it helps to drive more research in this area of study, which may ultimately benefit humans in the future.

Further reading:

Dominguez-Bello et al. 2016. Partial restoration of the microbiota of cesarean born infants via vaginal microbial transfer. Nature Medicine, doi.org/10.1038/nm.4039

This is a study that looks at restoring the microbiome of human infants, with only 4 subjects, comparing their microbiomes to those of c-section born infants. The conclusions are not very solid, but it opens the door to future studies that might be able to target only a few important taxa in humans.

- Jasarevic et al. 2015. Alterations in the vaginal microbiome by maternal stress are associated with metabolic reprogramming of the offspring gut and brain, Endocrinology, doi.org/10.1210/en.2015-1177

If you’re interested in reading the past study done by Jasarevic, when he first found a link between the gut microbiome and gut, read this study. It uses the same methods, and you can see how the authors led up to the current study and understanding of maternal stress effects on offspring health.

References:

- Rutayisire et al. 2016.The mode of delivery affects the diversity and colonization pattern of the gut microbiota during the first year of infants’ life: a systematic review. GMC Gastroenterology, doi.org/10.1186/s12876-016-0498-0

- Jasarevic et al. 2018. The maternal vaginal microbiome partially mediates the effects of prenatal stress on offspring gut and hypothalamus. Nature Neuroscience, doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0182-5

- Jasarevic et al. 2014. A novel role for maternal stress and microbial transmission in early life programming and neurodevelopment. Neurobiology of Stress, doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2014.10.005

- Martin et al. 2017. Births and natality. National Center for Health Statistics, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/births.htm

- Tamburini et al. 2016. The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nature Medicine, doi.org/10.1038/nm.4142

- University of Utah. (2011). Your changing microbiome. Learn Genetics, https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/microbiome/changing/

- Wikipedia. (2018). Fight-or-flight response. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fight-or-flight_response