Background

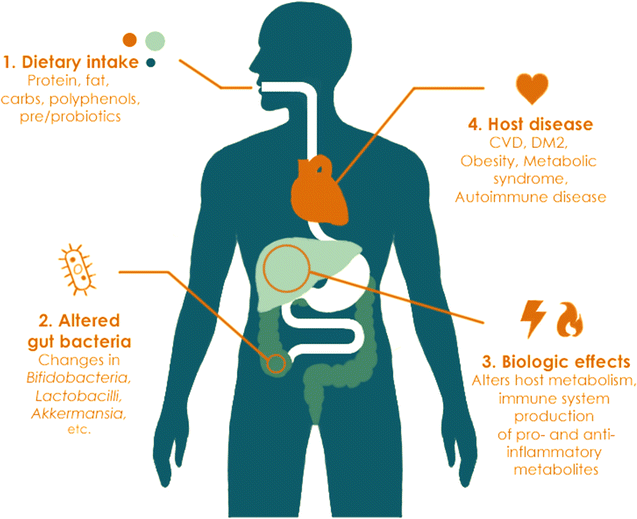

They always say that you are what you eat. In recent years, there have been an increasing amount of studies looking at the various microbes that live in and on you, and how your habits impact them. These large number of microbes are what comprises your microbiome. Understanding how they are impacted by lifestyle is becoming a well studied area of microbiology. Previous studies in this field have shown that certain types of these microbiota can have positive or negative effects on the overall function of an organism (Human Microbiome Project Phase II). Certain types of microbes have shown to be associated with various diseases of the gut. Many of these microbes have the ability to cause major health concerns among the human population, such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome, obesity, and autoimmune disease (Pittayanon et al., 2019 and Marietta et al., 2019).

Being able to characterize our differences based on diet can begin to help us be able to get our microbiomes to a “healthy’ state, (what is relatively healthy for the individual, not necessarily an overlapping term for everyone). This will also help with these diseases so they don’t plague the population in such high amounts as they do now. We can potentially do this through looking at the nutrient content within our chosen diets and how that diet relates to the number of microbiota and subsequently how those microbiota impact the body. That’s exactly what the authors of a recent study did (Losasso et al., 2018).

Central Question

Can the composition of diet make an impact on the abundance of certain types of microbiota (and how does that reflect the state of our gut microbiome)? To put it more simply, how does the gut microbiome change between omnivore, vegetarian, and vegan?

Evidence

Researchers set up the study so that all of the participants were roughly the same body mass index and age, so that the only significant difference between them was their choice in diet. The three diets (omnivore, vegetarian, and vegan) showed a very similar set of microbiota. The commonality between them (see figure below) made up the “core’ microbiota between all the diets. They all strived for a common nutrient uptake (carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins were all consumed about the same amount overall for each group), and the different types of food that changed between them did not affect this aspect very much. When it came to differences, omnivores and vegetarians, vegetarians had a greater diversity of microbiota (this was true between vegan and vegetarians as well). In other studies this seemed to be associated with healthier individuals (Chatelier et al., 2013 and Larsen & Claassen, 2018), but is debated (Lozupone et al., 2012) because it depends on which types of microbes are more abundant. All three diets had a high abundance of Bacteroidetes, which are associated with a westernized diet which has a low protein and carbohydrate content. Overall, though, it seems that you cannot really differentiate between the three groups based on composition of microbiota (despite the differences in what foods the nutrients come from), but it seems that we can begin to establish what kinds of diet lead to a more microbial-rich gut microbiome. Which will then, in turn, can only help with the other associated issues with the gut microbiome.

My Questions

How can we account for these differences in diet to bring them to a more standardized level that promotes a healthy functioning gut microbiome?

What did their diet look like specifically within each of the categories (like within vegan, was it just non-animal products vegan or did it include “raw veganism’ which does not include cooked food)? If this was looked at more, it would help with being able to understand how the lipid content was as high as it was within vegan (one would expect that it would have been lower than the other two groups).

How can the microbiomes within the groups that directly influence carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids change when you take into account when individuals develop diseases of the gut? Or what do the changes look like when the gut microbiome is “unhealthy’?

Further Reading

-

- A journal article on how quickly certain foods can change the kinds of gut microbes and how that impacts the host overall. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health

- Another journal article on how your diet can impact the gut microbiome, and in turn the associated diseases, by increasing certain types of microbes. Gut microbiome: profound implications for diet and disease

- A review of the literature that surrounds diet and gut microbiota. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota

- A cute animated video that summarizes what the gut microbiome is, what influences it, and how diet specifically can influence it. How the food you eat affects your gut – Shilpa Ravella

- Another overview of how the gut microbiome works, as well as the impact of certain characteristics within it. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiome

References

- Chatelier, Emmanuelle Le, et al. “Richness of Human Gut Microbiome Correlates with Metabolic Markers.’ Nature, vol. 500, no. 7464, 2013, pp. 541—546., doi:10.1038/nature12506.

- “Data Model.’ NIH Human Microbiome Project – Data Model, https://hmpdacc.org/ihmp/

- Hills, Ronald D., et al. “Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease.’ Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 7, 2019, p. 1613., doi:10.3390/nu11071613.

- Larsen, Olaf F. A., and Eric Claassen. “The Mechanistic Link between Health and Gut Microbiota Diversity.’ Scientific Reports, vol. 8, no. 1, 2018, doi:10.1038/s41598-018-20141-6.

- Losasso, Carmen, et al. “Assessing the Influence of Vegan, Vegetarian and Omnivore Oriented Westernized Dietary Styles on Human Gut Microbiota: A Cross Sectional Study.’ Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 9, 2018, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00317.

- Lozupone, Catherine A., et al. “Diversity, Stability and Resilience of the Human Gut Microbiota.’ Nature, vol. 489, no. 7415, 2012, pp. 220—230., doi:10.1038/nature11550.

- Marietta, Eric, et al. “Role of the Intestinal Microbiome in Autoimmune Diseases and Its Use in Treatments.’ Cellular Immunology, vol. 339, 2019, pp. 50—58., doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.10.005.

- Pittayanon, Rapat, et al. “Gut Microbiota in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome–A Systematic Review.’ Gastroenterology, vol. 157, no. 1, 2019, pp. 97—108., doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.049.

- Singh, Rasnik K., et al. “Influence of Diet on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Human Health.’ Journal of Translational Medicine, vol. 15, no. 1, 2017, doi:10.1186/s12967-017-1175-y.

- Zmora, Niv, et al. “You Are What You Eat: Diet, Health and the Gut Microbiota.’ Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, vol. 16, no. 1, 2018, pp. 35—56., doi:10.1038/s41575-018-0061-2.