The Gluten-free Diet

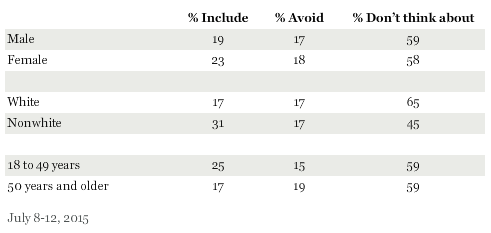

Celiac Disease is an autoimmune condition in which the immune system mistakenly attacks and damages the villi of the small intestine when it detects gluten. This damage can cause pain, fatigue, and diarrhea. If left untreated it can lead to complications such as infertility or cancer. Only a small number of people- around one percent of the population- actually suffer from Celiac Disease. A gluten-free diet is used as treatment for both celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Even though it is unknown whether a gluten-free diet is beneficial to people who do not have Celiac Disease, many people have adopted a gluten-free diet to eat healthier or lose weight. The number of people eating gluten-free is rising, with 17% of Americans actively avoid including gluten in their diet (Riffkin 2015).

How Does Gluten Affect the Microbiome?

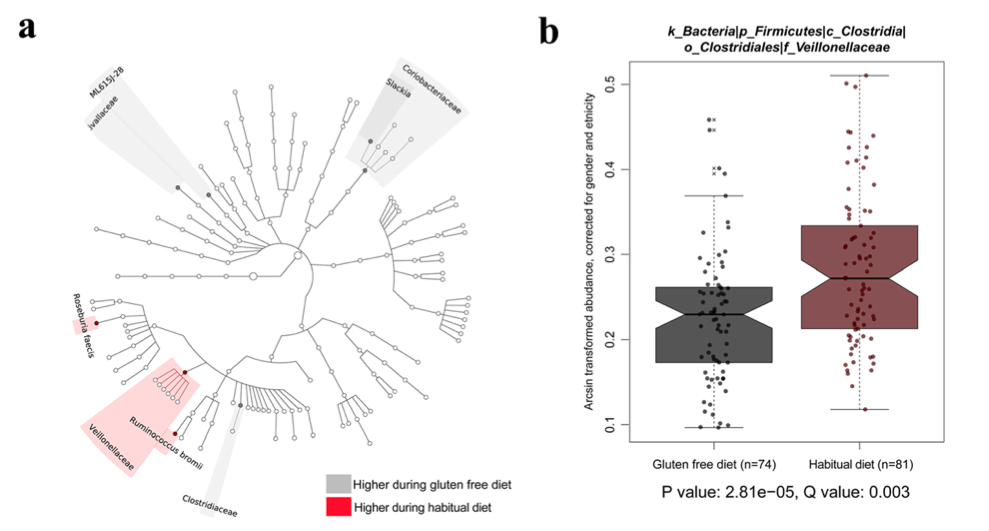

A study by David et al. (2014) found a significant difference in the gut microbial composition in humans eating an animal-based diet versus a plant based diet. Another study using mice found similar significant changes in gut microbes when the mice were fed a high fat diet (Cani et al. 2008). As microbiome research continues, one important question is whether the composition of gut microbes could be a contributing factor in intestinal diseases such as Celiac Disease, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, or colon cancer. In order to study the effect of a gluten-free diet on the gut microbiome, a group of researchers led by Marc Bonder from the University of Groningen in The Netherlands investigated how a short term gluten-free diet affects the microbiome (2016). Blood and fecal samples were collected from 21 healthy people who were placed on a gluten-free diet for four weeks. Samples were collected for another five weeks after the participants returned to a regular diet. The study found evidence that eight specific bacterial species changed in abundance during the gluten-free period (Fig 2a). Several of these species have been implicated in inflammation, which may be why people with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome find their symptoms ease on a gluten-free diet (Sokhol et al. 2008; Xavier and Podolsky 2007). Interestingly, the researchers were able to separate all but one participant into one of two categories based on bacterial gut composition: low species richness or high species richness. They found that while diet had an impact on bacterial composition, the species diversity between individuals was a larger factor.

Potential Confounding Factors

The bacterial composition of a core human microbiome has not been identified, which makes the results of this study more difficult to interpret. Several factors in this study- such as the background of the participants, who were from three different continents- could be potential confounding factors. Another possible factor is the energy source being consumed by the participants. Changes in diet have been shown to have a rapid effect on the composition of bacteria in the gut (David et al. 2014). Energy pathways being used by the microbial bacteria were slightly different on a gluten-free diet, possibly because carbohydrate intake was slightly higher in participants on the gluten-free diet. However, because there was not a significant change in energy source (i.e. changing from a mainly carbohydrate diet to a protein diet), there was not a significant change. This study was examining a change in the type of carbohydrate being consumed, which would be less likely to change the metabolic pathways used by intestinal bacteria.

It is tricky to determine how inflammation and the microbiome are related to one another. Patients with Crohn’s Disease have an altered gut microbiome, but it is unknown whether that is a cause or effect of the disease (Gevers et al. 2014). The participants on the short term gluten-free diet had a decreased number of several genera of bacteria. Most notably, the abundance of Veillonellaceae species was reduced (Fig 2b) . These bacteria have been associated with pro-inflammatory conditions. This suggests that a gluten-free diet did help to reduce bacteria that may be contributing to inflammation.

Connecting Diet and the Microbiome

Of course, microbiome research is so new that studies like this leave us with far more questions than answers. How is the microbiome related to the immune system? A 2009 study found that colonizing germ free mice with an altered gut microbiome left the mice with an unstable immune system (Round and Mazmanian). This suggests that certain bacteria help to regulate the immune system, and different bacteria could tip the immune system into either a pro- or anti-inflammatory response. Bonder et. al (2016) found that eating a gluten-free diet altered gut community composition. Unfortunately it isn’t possible to tell from this study whether the microbiome of a person eating a gluten inclusive diet is causing inflammation. A study done in 2012 found that the fecal bacterial populations of treated and untreated celiac patients were significantly different (Nistal et al). Untreated celiac patients had a significantly different microbiota from that of healthy adults, while treated patients had a more restored microbiome, with only a few differences from that of healthy adults. In the future, more research needs to be done on the relationship between inflammation, the microbiome, and the immune system. While diet can alter the microbiome, the effect it has on each person is highly individual, because each person is not colonized by the same microbes.

The authors of this study had difficulty understanding how inter-individual diversity affected their results. All 21 participants were from different backgrounds, which introduces even more confounding factors. Because a core human microbiome has not been established, it is difficult to tell whether there is an underlying problem in a person’s gut microbiome (Costello et al. 2009). The gut microbiome between people varies widely, however the community within an individual’s gut does not vary widely over time (Costello et al. 2009).

Further reading

Research concerning the relationship between gluten and the microbiome is very new, and as such, few studies have been published so far. However, to learn more about the topic, Dr. Bonder has published another paper about the effect of host genetics on the gut microbiome (Bonder et al. 2016). Another recent study looked at how infectious agents react with the microbiome to trigger an immune response in celiac disease (Rostami-Nejad et al. 2015). To learn more about Celiac Disease in general, this is a useful resource.

Literature Referenced

- Bonder, Marc Jan, Tigchelaar, E., Xianghang, C., Gosia, T., Cenit, M., Hrdlickova, B., Zhong, H., Vatanen, T., Gevers, D., Wijmenga, C., Wang, Y., Zhernakova, A. 2016. The influence of a short-term gluten-free diet on the human gut microbiome. Genome Medicine 8:45.

- Bonder, Marc Jan, Kurilshikov, A., Tigchelaar, E., Mujagic, Z., Imhann, F., Vila, A., Deleen, P., Vatanen, T., Schirmer, M., Smeekens, S., Zhernakova, D., Jankipersadsing, S., Jaeger, M., Oosting, M., Cenit, M., Masclee, A., Swertz, M., Li, Y., Kumar, V., Joosten, L., Harmse, H., Weersma, R., Franke, L., Hofker, M., Xavier, R. 2016. The effect of host genetics on the gut microbiome. Nature Genetics 48: 1407-1412.

- Costello, Elizabeth K., Lauber, C., Hamady, M., Fierer, N., Gordon, J., Knight, R. 2009. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 326(5960):1694-1697.

- Cani, Patrice., Biblioni, R., Knauf, C., Waget, A., Neyrinck, A., Delzenne, N., Burcelin, R. 2008. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high- fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57(6):1470-1481.

- David, LA., Maurice, CF., Carody, RN., Gootenberg, DB., Button, JE., Wolfe, BE., Ling, AV., Devlin, AS., Varma, Y., Fischbach, MA., Biddinger, SB., Dutton, RJ., Turbaugh, PJ. 2014. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505(7484):559-63.

- Gevers, D., Kugathasan, S., Denson, LA., Vasquez-Baeza, Y., Van Treuren, W., Ren, B., Schwager, E., Knights, D., Song, SJ., Yassour, M., Morgan, XC., Kostic, AD., Luo, C., Gonzalez, A., McDonald, D., Haberman, Y., Walters, T., Baker, S., Rosh, J., Stephens, M., Heyman, M., Markowitz, J., Baldassano, R., Griffiths, A., Syvester F., Mack, D., Kim, S., Crandall, W., Hyams, J., Huttenhower, C., Knight, R., Xavier, RJ. 2014. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe 15(3): 382-92.

- Nistal, E., Caminero, A., Vivas, S., Ruiz de Morales, JM., Saenz de Miera, LE., Rodriguez- Aparicio, LB., Casqueiro, J. 2012. Differences in faecal bacteria populations and faceal bacteria metabolism in healthy adults and celiac disease patients. Biochimie 94(8): 1724-9.

- Rostami-Nenjad, M. 2015. The Role of Infectious Mediators and Gut Microbiome in the Pathogenesis of Celiac Disease. Arch Iran Med 18(4):244-249.

- Round, June, Mazmanian S. 2009. The gut micro biome shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 9(5):313-323.

- Riffkin, R. 2015. One in Five Americans Includes Gluten-Free Foods in Diet. Gallup. <https://www.gallup.com/poll/184307/one-five-americans-include-gluten-free-foods-diet.aspx>

- Sokol, H., Pigneur, B., Watterlot, L., Lakhdari, O., Bermudez-Humaran, L., Gratadoux, J., Blugeon, S., Bridonneau, C., Furet, J., Corthier, G., Grangette, C., Vasquez, N., Pochart, P., Trugnan, G., Thomas, G., Blottiere, H., Dore, J., Marteau, P., Seksik, P., Langella, P. 2008. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohns disease patients. PNAS 105(43):16731-16736.

- Xavier, R., Podolsky, D. 2007. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 448:427-434.